The era of single-threaded human productivity is over.

Andrej Karpathy recently tweeted that he has never felt this much behind as a programmer. That sentiment reflects what I'm seeing in my own work as well.

Software engineering is going to radically change in 2026, for some people. Last Saturday, working across my side projects, I delivered what teams I've worked with would have estimated as at least 40 hours of sprint work, while barely touching my IDE. That is my new baseline.

The gap between "AI-native workflows" and "traditional engineering" is widening faster than most of us realize. As 2025 comes to a close, I want to break down exactly how that Saturday was possible, and why this level of velocity is about to become the new normal.

The great divide is already here

Plenty of engineers tried LLMs in the GPT‑4 era (or even just 12 months ago!), got mediocre results, and rationally decided "this isn't worth my time." The problem is that the tools (and workflows) changed underneath that conclusion, and a significant percentage of those engineers haven't updated their mental model of what's now possible. Many haven't tried Claude Code or similar tools, some don't see the value in a $100-200/mo subscription, others are sticking with free models and don't get to experience the state of the art, and still others have simply never revisited the question.

Earlier this year, I theorized that $1M salaries were coming for engineers1. The thesis is that as engineers become dramatically more productive, their value increases, and salaries follow. I still believe that, but I no longer think it'll come from established companies.

I think it'll come from new ones. Founders, solopreneurs, founding engineers. People whose job will be giving AI the right guardrails, context, and environment to perform (we could call it LlmEx, like DevEx). Companies that hire one engineer expecting five engineers' worth of output. And experienced engineers who can actually assess AI output, not just vibe code, will be worth their weight in gold. That's my bet, anyway.

What our job will become

But engineer performance is increasing. AI has gotten genuinely useful. A lot of us have already seen that it's incredibly good at greenfield projects - spinning things up from scratch, putting together a little MVP of whatever it is you're wanting to build. On its own, though, it can struggle to maintain long-running projects. Making it come into an existing codebase blind works much more frequently than I would expect it to, but it doesn't always. And for those situations, it's important to establish the right foundations and guardrails for LLMs (automated tests, static typing, linting, anything that catches mistakes before runtime). Doing so will make AI perform better, and it will force us to write good code.

In my opinion, in the near future, our job description will evolve into:

- Be the architect laying the foundations to enable AI to be successful in your project.

- Keep up with developments in the AI world and consistently look for ways to enable AI to be more productive. A month is a long, long time in the AI world.2

- Manage as many concurrent AI agents as you can to deliver as many tasks as possible as fast as possible.

That last one is what I think is the big productivity shift for engineers. And what does this actually look like in practice? I'll use myself as an example; this is how I've set up my environment to enable this parallelization:

Embarrassingly parallel programming

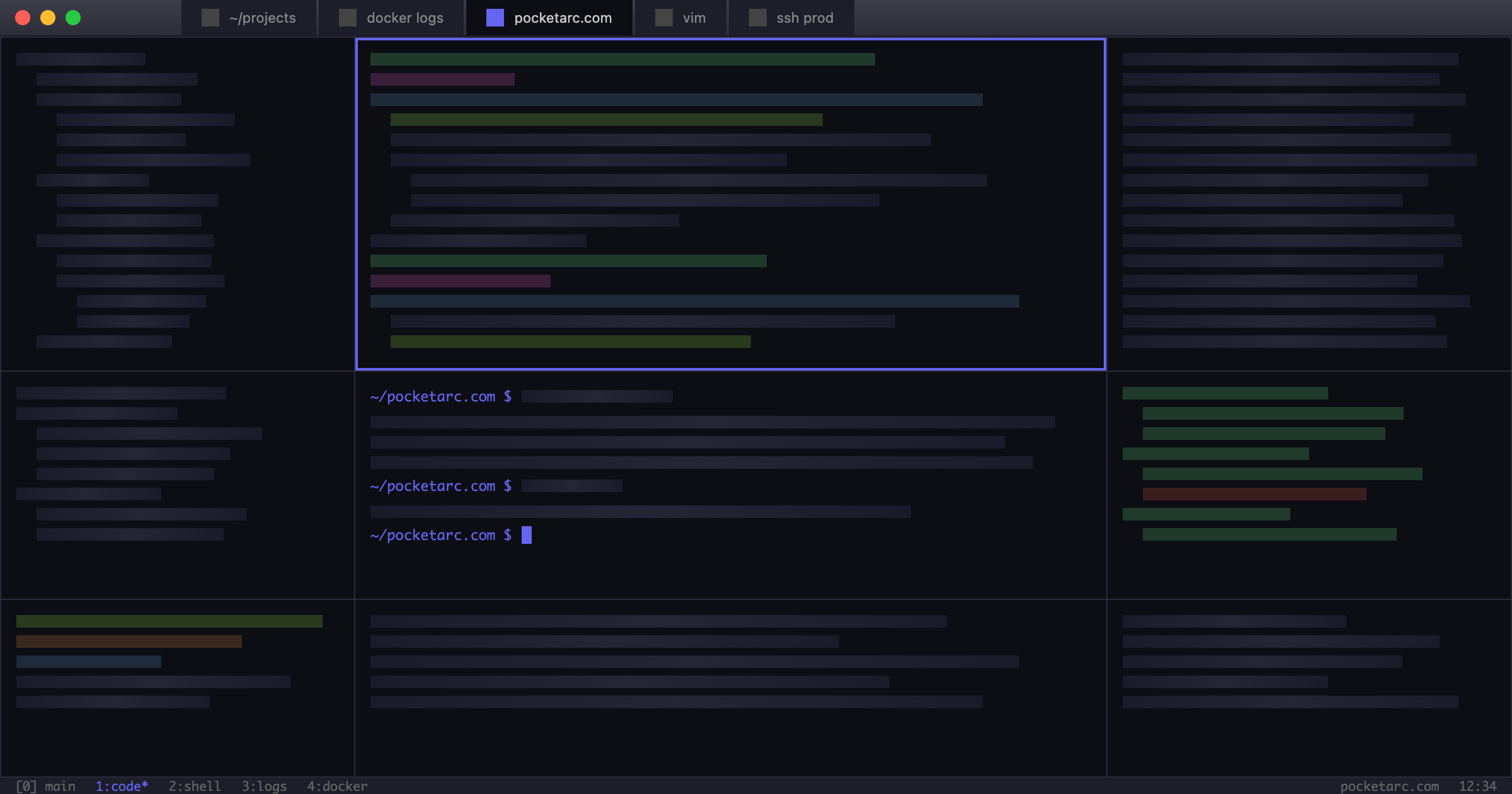

Over the past ~6 months, I've orchestrated all of my projects with docker-compose.yml, so that I can easily spin up multiple copies of a project, each with its own dependencies and the right versions of whatever services they need. I can have 5 copies of a git repo running 5 different copies of the project simultaneously, so Claude Code can work on separate tasks without any of them affecting any other work being done. Having them fully separated has been an incredible boon. I can run tests separately, I can have different browser tabs open for manual testing each different version of the project, I can review everything in separate PRs, it all works really well.

And it didn't take much effort: Using AI to generate the Docker files and configs in the first place means that you don't even have to deal with the cognitive effort of putting those together.

Some people use git worktrees for this, which I haven't tried, but I think that would make manual testing far more complicated than just having 5 docker compose up -d copies running at the same time. On my Mac, I've been using OrbStack, which automatically manages networking for them all, so I can go to project1.orb.local, project2.orb.local, and so on, without having to set anything up. They're all completely separated without me having to do anything.

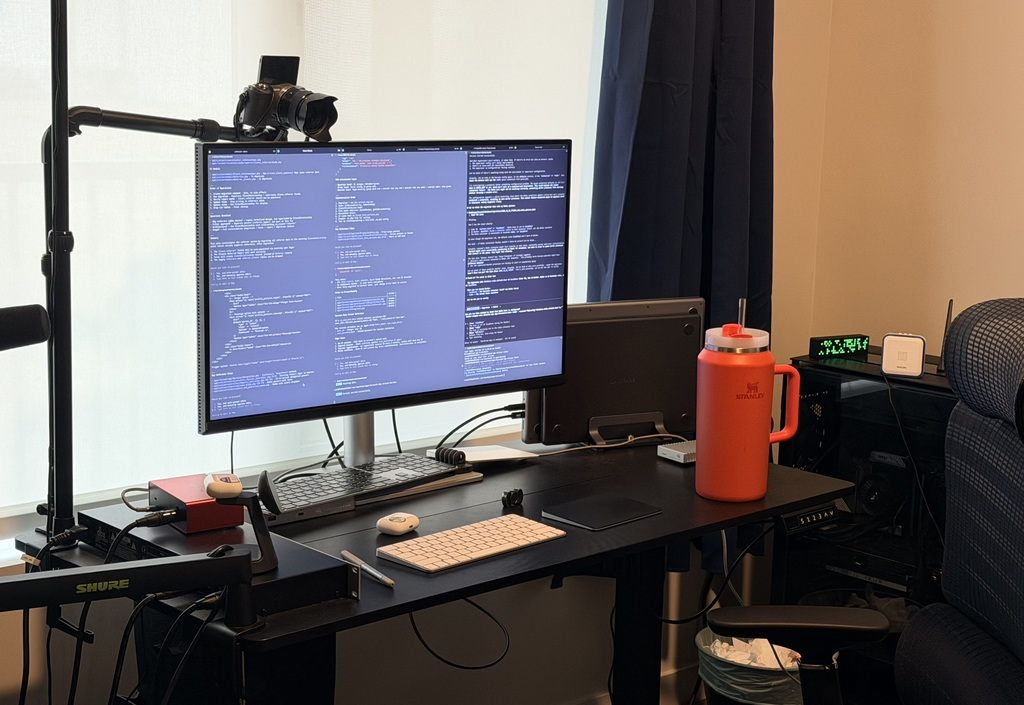

Imagine what you could do if you could have all those copies of your project up at the same time, and you had 3 monitors so you could manage your Claude Code instances and test everything all at the same time. That's the setup.

I put together a small simulator to demonstrate why this works. Even if the AI is dumber than you, even if it takes you a lot longer to get through tasks with it or explain things to it, the moment you spin up a few concurrent agents, the math shifts aggressively in your favor:

Throughput vs. Latency Simulator

Even if using AI takes longer than doing it yourself, parallelism wins.

Tickets were designed for humans

Most engineering work revolves around tickets. Discrete units of work that get estimated, assigned, and shipped. Bigger pieces get broken into smaller ones. Think about all the tickets that you see at your work. Really think about them. A new piece of functionality here, a change to existing functionality there, that kind of stuff. Most tickets just aren't that complicated.

And this is exactly where I see the big shift between engineers who wield AI and those who don't. State-of-the-art models and tools like Claude Code have gotten us to a point where you could realistically work on 10+ different tickets all at the same time.

You would run a bunch of separate AI agents, work with them to come up with a plan for all of those tickets, and then just grind through them all. Unlike a human being, separate AI agents don't have to switch contexts. They can go read through 100 different files in your repository, they can dig into things for you, they can keep the task in mind and get through it.

A human being would just flat out not be able to grind through so many disparate pieces of work that quickly. Humans need time to think things through, understand the context, go look through the code, and make their way through. It's even worse if you're looking at tickets for entirely separate projects. What human is capable of working on different codebases simultaneously and legitimately be productive? I would love to meet them.

But AI can do it without breaking a sweat.

What 40 hours on a Saturday looks like

Regardless, when it comes to fully autonomous agents, I'm not quite there yet. I've never used --dangerously-skip-permissions (if you're not familiar, it's a YOLO mode that gives the agent full permission to do anything and everything on the computer), and I haven't left an AI to figure things out on its own yet. For now, I've been paying attention to everything all my different agents are doing. Quickly reading through the code they're putting out, sense-checking what they're doing and steering them in different ways if I'm not happy with whatever direction they're going in3.

If the plan is "change function X to support Y and update component Z to display that in a modal", all it takes is a few seconds to glance at the code for those in the Claude Code terminal, and understand that "yep, looks good". It's not "it takes me longer to review than it would if I wrote it myself", and especially not when you take into account the cost of context switching and the cognitive load of trying to grasp the context for whatever change you need to make.

After that, services like CodeRabbit can do a 1st-pass code review for you4. Between the automated code reviews, linting, static analysis, static typing, automated testing, and all that malarkey, the code is solid, and you can be sure it does whatever you agreed to do during your planning phase. You do some manual testing, make sure everything looks good, do a final self-review, make sure you're happy with everything that's been done, and then raise a PR.

I have already seen the performance shift for myself: Thanks to my current setup, I can now deliver what my team would estimate as 40 hours of sprint work in a single Saturday.5 That's 40 hours of ticket estimates: the kind of tasks that would take a week of focused work for one engineer, spread across maybe 8-10 discrete tickets. A frontend component here, a backend endpoint there, a migration, some test coverage. None of them individually heroic. All of them done. It's surreal. The amount of time that I spend in my IDE has collapsed. I can spend a whole day "working" but only ~15 minutes in my IDE. I'm just managing agents all day.

A side project of mine hadn't been updated in 5 years, and one of the APIs it used was being sunset. I needed to update it to use the new version of the API. But for that, I would need to 1) go read through upgrade guides, 2) go read through the new API docs, and 3) go get the project up and running again in the first place. Not difficult, and not technically challenging work. Just tedious low-priority maintenance work. I got a couple Claude Code instances working through the upgrade, and it all got done, with almost no cognitive load, and while I was also working on other things. I'm not the only one finally making progress on long-backlogged tasks.

And because I was keeping a casual eye on what Claude Code was doing, I actually got to see the changes it made and have a general idea of what it took. It's not super in-depth knowledge, but that would be the same situation you'd be in if you were leading a team and tasked a teammate with doing the upgrade ticket. In fact, if you assigned it to someone, you would have zero visibility into it, but if you're reading through what Claude Code does, at least you see it happening and can follow along.

To me, that's been very valuable for maintaining an understanding of the codebase.

And: It was faster with AI than it would've been if I had done it myself. But even if it wasn't, it took very little cognitive load to get through that upgrade. I was working through it as 1 of 10+ different terminal tabs I had open, working through 10+ different tasks for different projects.

The cost is cognitive, not technical

The benefit of agentic AI isn't that "it will do it faster than you", it's that it unlocks parallelization. You can be working on as many tasks as your brain can handle at the same time, limited only by your context-switching skill. The era of single-threaded human productivity is over.

And I'll admit: That is where I struggle the most - it's insanely demanding to spend a day jumping from task to task, guiding Claude instances in the right direction and making sure they all achieve their goals.

Part of me thinks that if that becomes a normal performance expectation, a lot of us will burn out. Myself included - sustaining this level of performance for weeks at a time feels like it will get obscenely exhausting.

For now, though, this level of performance makes me feel superhuman and enables me to tackle a lot of things that otherwise would have to wait. That's been satisfying. If I were building my own startup, this is exactly what I would leverage to the extreme to keep the team as lean as possible. Building is no longer the bottleneck.

Adam Wathan (creator of Tailwind CSS) recently asked: "Is there anything you've built that's been game changing for your business that was just impossible to justify pre-AI?" A lot of us are starting to answer "yes." Features that died in backlog purgatory, maintenance work that never made the sprint, side projects that sat abandoned for years, that's all doable now.

Three headwinds for 2026

As an engineer, my philosophy has always been: The more things I can be told are wrong automatically, the better. I don't want anything to break at runtime that I could've been warned about in advance. That's why I'm in love with Rust, static typing, TypeScript, static analysis tools, Result<T, E>6, and even IntelliJ IDEA's inspections. For a long time, IDEA was always so much more powerful than what you used to get from other editors that I couldn't imagine living without it. And now all those guardrails for humans are even more impactful than I could ever have imagined.

2026 will be a scary year for engineers. I think founding engineers have a leg up here, because without an entrenched process, they can immediately start taking advantage of the massive parallelization of work, and move faster than ever. But engineers at established companies will be going up against three headwinds:

- Most corporate processes assume a human is doing things by hand. Ticket estimation and sprint planning come to mind; those pipelines aren't set up for "I could feed 10 feature requests to AI to make an initial draft plan for what it'd take to implement, and come up with a very rough estimate in a few seconds".

- Part of their team hasn't bought in, and doesn't intend to. This creates a painful asymmetry: you can't build a process around AI-level output velocity if half the team is working at human speed. Someone ends up on a PIP, or the team fractures into two tiers. Neither is fun.

- Their existing project(s) don't have the necessary guardrails in place, and adding them would be a lengthy process that they don't want to invest in. If your project's never even had automated tests of any kind... using AI to develop anything will require some serious faith.

I don't think engineers are going anywhere. There are still plenty of things that are just too complicated for an LLM to reason through, where it fails (some gnarly business logic bits, or whatever it is). But the % of time that you, as an engineer, do that kind of complex work, vs work that can easily be done by an LLM, is already quite low, and only getting lower.

Obviously, this depends on the kind of work you do. If you're working on low-level assembly optimization for embedded systems, it may be that 100% of your work has to be done by hand, and LLMs are of no use right now. That's OK, and completely understandable. But most of us building software aren't doing anything near that complicated.

For most of us, the earthquake has already hit, and the tsunami wave of change is coming.

As William Gibson once wrote that "the future is already here - it's just not very evenly distributed."

I’m curious about everyone's thoughts on this. I'm always excited to talk about this stuff, so feel free to reach out to me directly either on X/Twitter @pocketarc or by email.

Fun fact: The cover image for this post was made with HTML & CSS, not an AI image generation model. Neat, huh?

Footnotes

-

Not published. And now re-reading, it's out of date, alongside a few other articles I was halfway through writing throughout the year. I'm learning (too slowly) that AI moves too fast for me to procrastinate on hitting that "Publish" button. ↩

-

For AI, I mostly rely on Shawn Wang's (@swyx) smol.ai daily newsletter; it provides a daily summary of whatever's gone on for the day in the world of AI. I spend 30 seconds skimming it, and I'm done. It's been a godsend for how easy it makes keeping up. ↩

-

That's probably the reason I only rarely hit Claude limits even on the $100/mo plan - I don't just leave it to burn through tokens. ↩

-

I have to admit, I'm a latecomer to AI code reviews: I tried CodeRabbit for the first time this month, and it's been unbelievable. It spots a lot of things most reviewers would miss and is very easily teachable (just back and forth in PRs). It can serve as a great 1st pass code review before a human goes in for a real code review. ↩

-

A common response to claims like this is "where's all this productivity, why don't you share what you've built?" The reality is that most of us work on things that aren't open source. Features just ship faster, startups spin up faster, improvements are made that otherwise would sit in a backlog, and teams do more with the same people. Look at Anthropic's own release velocity, or Simon Willison's point about rolling functionality into your project rather than pulling in a

left-paddependency. ↩ -

Result has completely changed how I think about error handling. If you're not familiar with it, it's worth a look. ↩